With each passing week, it seems audiences are treated to a new superhero movie or television series. Marvel and DC Comics, known widely as “The Big Two,” have been churning out hit after hit over the past several years, but America’s fascination with superheroes dates back to a time when feature films were still in their formative years.

In 1938, American audiences were introduced to the first superhero, Superman, who became the first comic book character to have powers beyond the normal human. Since then, the industry has exploded with comic book characters featured as in movies, television, video games, and as kids’ favorite action figures. This staying power can be traced back to one crucial element: a storyboard – or “superboard,” if you will.

But what is the relationship between comic book artists and storyboard artists and can one find success in both? I spoke with Artist Sean Chen, a Famous Frames storyboard artist and contracted comic penciler for Marvel Comics about his work within both industries and his insight goes above and beyond…

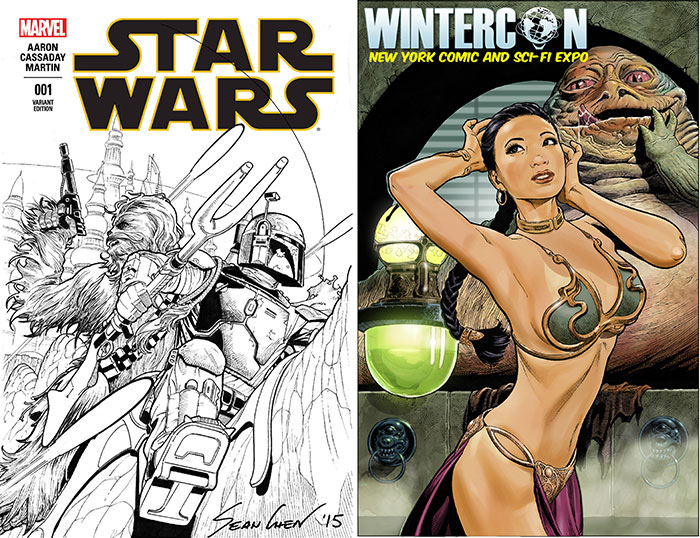

SEAN CHEN’S STAR WARS COVER FOR MARVEL & WINTER NY COMIC & SCIFI EXPO YAYA HAN PRINCESS BY SEAN CHEN.

JQ: How do comics differ from storyboarding?

SC: The general skill of visual storytelling is practically the same. The main difference is that what I would draw in comics is the end product. Storyboards, however, are a step in a larger process where the end product is something filmed. We’re basically behind the scenes. So the art in comics needs to be much more refined and detailed, and visual appeal of the art is very important.

JQ: How did you get your start in the comic industry?

SC: It was about 2 decades ago; I would make an annual trip to the San Diego Comic Con bringing an ever-evolving portfolio of sample work. The goal was to get hired as a comic book artist, but what I often came home with was a bunch of advice and feedback. This was fine because it was valuable information that helped me get closer. Eventually I landed my first job at a company called Valiant comics.

JQ: What interested you about Comic Con and how did that benefit you as an artist?

SC: There are a myriad of reasons I would attend Comic Con. The main reason is to promote whatever I’m working on. Beyond that, it’s a great chance to interact with the fan base and get feedback from them. Much of the future work I would line up happens at Comic Con since editors from all the major comic companies attend. It’s also a great for reuniting with and meeting fellow artists to hang out or talk shop. I can also use the cons for taking on commission work and making money.

JQ: What is the creative process of creating a comic?

SC: Usually the breakdown is, there’s a writer who provides a full script, which is much like a movie screenplay. Then it would be given to the penciler who translates that written script into a visual story. These penciled pages are usually then passed on to an inker who solidifies and refines the artwork by turning gray pencil lines into solid black ink lines. Then the colorist is brought in to add the colors digitally. The last person involved is the letterer who puts all the dialogue into the word balloons as well as creating those trademark sound effects. The whole process is overseen by an editor who keeps everything on track.

JQ: What materials do you use to draw comics?

SC: For most of my career it was as simple as paper and pencil. Marvel would provide the paper stock, and I drew with a mechanical pencil. This meant that the only supplies that I was responsible for was pencil leads! I am primarily a penciler, which means that I usually work in a team where other artists are responsible for the inking, coloring and lettering. It’s only been in the last 5 years or so that I adopted digital elements to my workflow. These days I have a Wacom Cintiq and Photoshop as part of the process.

JQ: How do you determine the blocking and composition of the frame in comic books?

SC: Ultimately, the story determines the composition within those panels, while taking into consideration the special constraints of comics as a medium. Comics are handicapped by not having movement or sound which usually are important elements that clue you in to what exactly is going on in the story. In general, a comic book artist would have to zoom in and crop out any extraneous elements that could confuse the point of the panel. There are also artistic decisions made through the handling of the composition of elements or shading which can help lead the eye to the focus of the panel. This visual storytelling ability is the most important skill that a comic book artist brings to the table. Composing a scene in comics is quite different from how it would be handled in film. We really have to be expert visual storytellers.

JQ: Why do you think more comic book artists become interested in storyboarding?

SC: Veteran comic book artist are very well versed in communicating through images, which is why they are such a good fit for storyboarding. The main reason [comic book artists become interested in storyboarding] would probably be more money. Sadly, comics, as an industry, don’t make much money. It’s their film and merchandising counterparts that do, but all those profits don’t filter into the publishing arm that those characters and storylines are born from. Add to that, the sheer amount of very finished art that needs to be produced on a monthly basis, and you can see that it can be quite a grind for that amount of money. Contrast that with the advertising industry where budgets can be huge because profits can be huge especially if a successful campaign is involved. The artwork is also much less labor intensive since a high level of finish or detail is usually not called for. There is also the appeal of doing work in movies or television that reaches more people, and can be very creatively rewarding but in a different way.

JQ: What do you think determines whether a comic book artist will be successful transition into storyboarding?

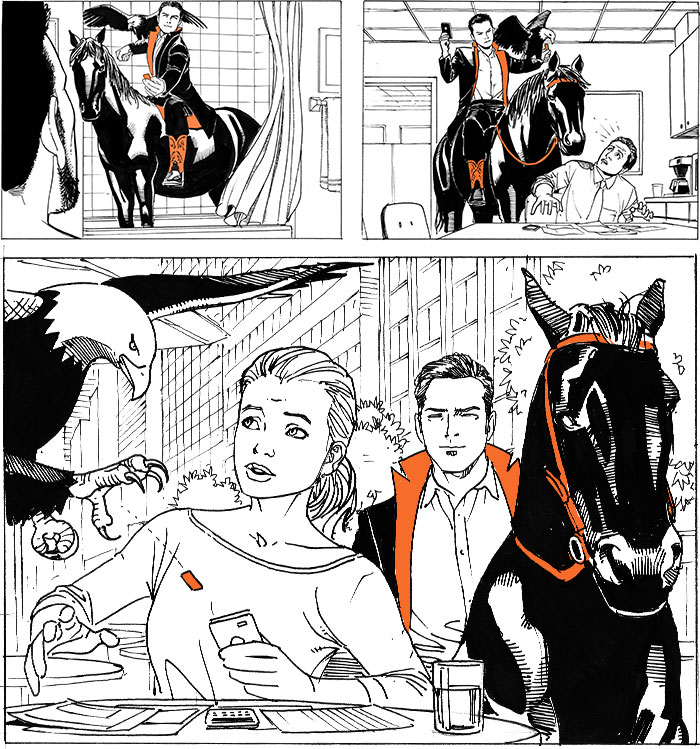

SC: I think it comes down to two factors: attitude and ability. In comics, the artist is like the celebrated lead singer of a band. Your art is the final product that gets seen, and you can build a fan base. Storyboarding is not like that. You are definitely more part of the development process and the end product is something filmed. If you’re an artist that likes to be in the spotlight, you may find it hard to thrive in storyboarding. It has been said that there are two types of artist in comics. Artists who draw comics, and comic book artists. It’s better to be the latter. Many comic book artist can only draw comics, and struggle when it comes to drawing real life people in realistic situations. Superhero comics are “larger than life” characters and storylines. This type of art is often so ingrained in the DNA of a comic book artist, that any other way of representing life is not possible. In general, as a storyboard artist, you are assisting in the needs an agency or production company. It’s not about you, and your art and attitude has to reflect that.

JQ: What would you suggest to those comic book artists who want to transition into storyboarding?

SC: A comic book artist really needs to check him or herself. Know if you are ok leaving behind the trappings of the comic book industry. How much appeal did drawing superhero slugfests, having a fan base, and comics as a storytelling medium have for you? If you only ever learned to draw by imitating other comic book artist, you had better start transitioning to representing real life. Bring over all the expertise you’ve gained in visual storytelling, but many of the stylistic flairs that made you a celebrated comic book artist may only pigeon-hole you in the ad world.

SEAN CHEN’S STORYBOARDS FOR AN AMAYSIM SPOT.

JQ: Can you tell us about your experience transitioning from comic book artist to artist who draws comics?

SC: When I made the switch from comic book artist to being primarily an advertising artist, I thought I would be saying goodbye to the dynamic art of superheroes in favor drawing ordinary people holding up shampoo bottles or food items. Ironically, I seem to draw just as much superhero stuff since the movies are such a big business and have found their way into every aspect of our daily lives. I get typecast as the ad artist that had an entire career at Marvel and therefore get much of the superhero related ad work funneled to me. It’s great because I don’t have to miss drawing that genre at all. Funny thing is that I actually really like drawing ordinary people holding up shampoo bottles or food items!

JQ: Describe your style of comics (what makes your comic style different from others)?

SC: I tend to draw more realistically than most artists. I really don’t do too much of the cartoony stuff. I think its because I tend to take the stories too seriously. That’s kind of slowly changing in recent years as I come to appreciate cartooning more and more. I have a fairly meticulous style. Lots of detail and rendering. I also take the storytelling aspect very seriously. Comic must tell present a story clearly without confusion and in an interesting way.

JQ: Marvel or DC? Why?

SC: I’ve always been partial to Marvel. It’s where the lions share of all output has come from. I just know the editors, and the characters better.

See more of Sean Chen’s work HERE.