There was once a time when you had to explain what a storyboard artist was. This was back in the pre-digital days of paper and markers when most assignments were performed in-house. Fax machines and pagers were the technological advances most affecting the industry. Demand well exceeded supply and artist fees were accordingly raised annually. It’s a different world today.

I’ve represented storyboard artists for over thirty years and counting. Back in those earlier days, my company would receive about thirty artist submissions a year. These days, we average five submissions per day, everyday. That’s over 1,200 applicants a year! This deluge of artists started building slowly in the mid nineties, fueled by two unrelated events: the internet which introduced untapped worldwide clientele along with ever increasing worldwide competition and the blockbuster animation revival which eventually led to colleges and art schools recognizing the lucrative demand for such classes for a soon-to-be over saturated job market. However, despite this overwhelming increase in portfolios, I find the number of qualified storyboard artists has remained essentially the same. Therefore, for the sake of saving time and effort for all parties, I’ve complied a few suggestions for storyboard artist submissions.

If you’re applying for either storyboard representation or a storyboard position, then SUBMIT STORYBOARDS. This advice may be glaringly obvious but you’d be surprised by the large percentage of submissions consisting entirely of fine art, editorial illustrations, nude sketchings, children’s and comic books, even (I kid you not) sculptures. While this may be an indication of one’s artistic talent and diversity, it doesn’t show whether you have the skills needed to perform in a high pressure industry for ever changing clients, products and personnel under (in many cases) strict “due yesterday” deadlines.

Research the company/agency you’re submitting to. Visit their website. Study their artist roster. These are your peers. These are your competitors. Are you in their talent range? If not, then wait until you are or find a more suitable B-list or “good enough” company. If your particular style is too unique or not represented on their website that most likely is not a good sign. Unlike fine art, storyboards adhere to a compatibility factor. Assignments are often done in conjunction with other artists. In many cases, you’ll be revising boards done by a previous (now unavailable) artist. Boards may be “tight” or “loose”, “realistic” or “cartoony”; but rarely if ever “unique”. Among the most in-demand storyboard artists are those who have the chameleon-like ability to match other artist styles.

It should be noted: I’m referring to advertising storyboards used for presentation purposes. Film and production boards are directorial tools, a shooting blueprint for camera angles and continuity. Film knowledge and experience are essential. There are often union considerations for employment or representation as well. Animation storyboards seems to be what’s being taught most in art schools today. (I can’t recall seeing advertising boards coming from a college portfolio.) Unfortunately, most of this work went overseas years ago and does not translate to commercial boards.

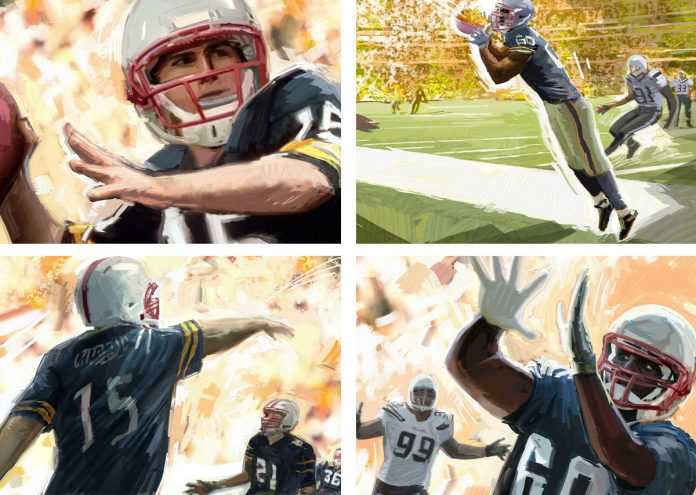

Identify what areas are your forte or strong suites. Are you good with automotive, food, product or people services? Most commercials and print ads fall within these subject categories. Fashion, environmental and architectural renderings, caricatures & likenesses are also frequently requested advertising specialties. Most artists excel in one or two particular areas. The more diversified your abilities, the more assignment options you’ll encounter.

Maintain an up-to-date portfolio. There is an unfortunate (though denied) undercurrent of ageism in this industry, so replace dated products and celebrity boards. Unlike in film production, there’s no IMDB-like resource to check credits for commercial storyboards. While I’m not suggesting taking credit for agency boards you never drew, it is useful to render your own versions from these primetime commercial scripts. Make sure to change some of the angles. Change the characters too. Remember, you allegedly drew these boards before the commercial was shot. Study the shot sequence, usually between eight to ten frames per 30-second commercial. That should average an eight-hour day’s work. (Five to eight color frames in an eight-hour day for color, estimated at one to one and a half hours per frame.)

As is often the case, job parameters change in mid-assignment. Frames can be added. Budgets and deadlines shortened. You’ll need to adjust your frame speed and quality to meet this newer reality. In the past, I’ve given sample scripts to aspiring storyboard artists only to have them return weeks or even months later with beautifully rendered boards. Unfortunately, these are of no benefit in determining whether an artist can perform under actual work conditions. You’ll need to show what your workload looks like under a normal day’s deadline. How about the same frame amount performed in half the time? Complex boards with multiple characters and environments will naturally take longer. Time yourself and indicate how long each piece took to draw.

Most important, be true to yourself. Don’t oversell your abilities. Even the most loyal clients have a short memory. You’re only as good as last assignment.

In closing, I’d like to relate the most outrageous submissions war story I’ve encountered yet. It occurred about two years ago. We received a fantastic portfolio and representation request from an L.A. based artist. I eagerly called and arranged a meeting at our office. He was a pleasant guy in his early thirties, eager to work in-house or at home, flexible on budgets and schedules. An ideal artist to represent. We shook hands and agreed to work together. The problem came later that day when a staff member noticed some of the submitted work looked familiar. Seems a few frames were lifted from other artists we represented (famousframes.com). A Google image search revealed other portfolio pieces “borrowed” from the competition’s aces and the cream of national and worldwide independents. Needless to say, my subsequent phone message and email was never returned. I can’t fathom how this con artist expected to survive an actual assignment imitating these professionals under normal battle conditions. I don’t know if he was ever able to sucker another agent into representing him. I do know one thing for sure. This applicant had a great eye for talent.

MCM

[Mark C. Miller is the President/Co-owner of storyboard agency Famous Frames, Inc. since 1988 and a storyboard statesman.]

“There’s really nothing to becoming an elder statesman. You just don’t die, and you hang around” – John Hiatt (musician/songwriter)